By Leslie D’Monte

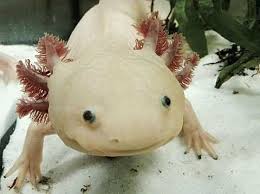

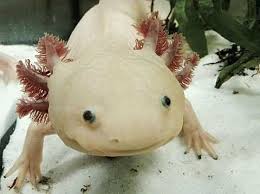

Humans may share genes with lower organisms but they do not share the miraculous ability to regenerate form and function of almost any tissue after injury the way lower organisms do. Soon, we might find a way to do so, thanks to the efforts of scientists at the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, who are studying the genetics of these organisms to find out how regenerative mechanisms might be activated in humans. In a paper published in the journal PLOS ONE, MDI Biological Laboratory scientists Benjamin L. King, Ph.D., and Voot P. Yin, Ph.D., identified common genetic regulators in three regenerative species: the zebrafish, a common aquarium fish originally from India; the axolotl, a salamander native to the lakes of Mexico; and the bichir, a ray-finned fish from Africa. The discovery of the common genetic regulators is expected to serve as a platform to inform new hypotheses about the genetic mechanisms underlying limb regeneration, the scientists said in a 5  August press release. The discovery also represents a major advance in understanding why many tissues in humans, including limb tissue, regenerate poorly — and in being able to possibly manipulate those mechanisms with drug therapies. The discovery of genetic mechanisms common to all three of these species, which diverged on the evolutionary tree about 420 million years ago, suggests that these mechanisms aren’t specific to individual species, but have been conserved by nature through evolution. “I remember that day very well — it was a fantastic feeling,” said King, adding: “We didn’t expect the patterns of genetic expression to be vastly different in the three species, but it was amazing to see that they were consistently the same.” In particular, the scientists studied the formation of a mass of cells called a blastema that serves as a reservoir for regenerating tissues. The formation of a blastema is the critical first step in the regeneration process. Using sophisticated genetic sequencing technology, King and Yin identified a common set of genes that are controlled by a shared network of genetic regulators known as microRNAs. The study also has implications for wound healing, which, because it also requires the replacement of lost or damaged tissues, involves similar genetic mechanisms. With a greater understanding of these mechanisms, treatments could potentially be developed to speed wound healing, thus reducing pain, decreasing risk of infection and getting patients back on their feet more quickly. Another potential application is development of more sophisticated prosthetic devices. When a limb is amputated the nerves at the site of amputation can be damaged. The repair and regeneration of these nerves could potentially enable the development of more sophisticated prostheses that could interface with these nerves, allowing for greater control. While speedier wound-healing and improved prostheses may be on the nearer-term horizon, the ability to regrow limbs is a long way off. How long? “It depends on the pace of discovery, which is heavily dependent on funding,” Yin said. The ability of animals to regenerate body parts has fascinated scientists since the time of Aristotle. But until the advent of sophisticated tools for genetic and computational analysis, scientists had no way of studying the genetic machinery that enables regeneration. These tools, coupled with the efforts of such scientists, now give hope to humans who lose their limbs.

August press release. The discovery also represents a major advance in understanding why many tissues in humans, including limb tissue, regenerate poorly — and in being able to possibly manipulate those mechanisms with drug therapies. The discovery of genetic mechanisms common to all three of these species, which diverged on the evolutionary tree about 420 million years ago, suggests that these mechanisms aren’t specific to individual species, but have been conserved by nature through evolution. “I remember that day very well — it was a fantastic feeling,” said King, adding: “We didn’t expect the patterns of genetic expression to be vastly different in the three species, but it was amazing to see that they were consistently the same.” In particular, the scientists studied the formation of a mass of cells called a blastema that serves as a reservoir for regenerating tissues. The formation of a blastema is the critical first step in the regeneration process. Using sophisticated genetic sequencing technology, King and Yin identified a common set of genes that are controlled by a shared network of genetic regulators known as microRNAs. The study also has implications for wound healing, which, because it also requires the replacement of lost or damaged tissues, involves similar genetic mechanisms. With a greater understanding of these mechanisms, treatments could potentially be developed to speed wound healing, thus reducing pain, decreasing risk of infection and getting patients back on their feet more quickly. Another potential application is development of more sophisticated prosthetic devices. When a limb is amputated the nerves at the site of amputation can be damaged. The repair and regeneration of these nerves could potentially enable the development of more sophisticated prostheses that could interface with these nerves, allowing for greater control. While speedier wound-healing and improved prostheses may be on the nearer-term horizon, the ability to regrow limbs is a long way off. How long? “It depends on the pace of discovery, which is heavily dependent on funding,” Yin said. The ability of animals to regenerate body parts has fascinated scientists since the time of Aristotle. But until the advent of sophisticated tools for genetic and computational analysis, scientists had no way of studying the genetic machinery that enables regeneration. These tools, coupled with the efforts of such scientists, now give hope to humans who lose their limbs.