Who is liable if there is an accident involving a driverless car and a human driver? If both parties are liable, how should the accident loss be apportioned between them?

Researchers at Columbia Engineering and Columbia Law School believe a joint fault-based liability rule can be used to regulate both driverless car manufacturers and human drivers. Their findings were presented on January 14 by Sharon Di, assistant professor of civil engineering and engineering mechanics, and Eric Talley, Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law, at the Transportation Research Board’s 99th Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C.

Their research was spurred by a recent decision by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) on the March 2018 Uber crash that killed a pedestrian in Arizona. The NTSB ruling split the blame among Uber, the company’s autonomous vehicle (AV), the safety driver in the vehicle, the victim, and the state of Arizona.

Game theory to the rescue

The Columbia researchers note that while most current studies have focused on designing driving algorithms in various scenarios to ensure traffic efficiency and safety, they have not explored human drivers’ behavioural adaptation to driverless cars, also known as AVs.

“Human drivers perceive AVs as intelligent agents with the ability to adapt to more aggressive and potentially dangerous human driving behavior,” says Di, a member of Columbia’s Data Science Institute, in a January 13 press statement. “We found that human drivers may take advantage of this technology by driving carelessly and taking more risks, because they know that self-driving cars would be designed to drive more conservatively.”

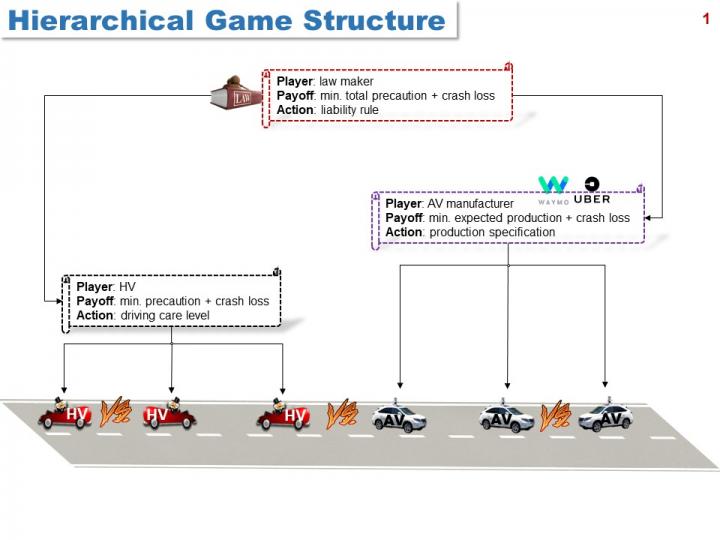

The researchers used game theory to model a world with interacting players who try to select their own actions to optimize their own goals. The players–law makers, AV manufacturers, AVs, and human drivers–have different goals in the transportation ecosystem.

The hierarchical game helped the team to understand the human drivers’ moral hazard (how much risk drivers might decide to take on), the AV manufacturer’s impact on traffic safety, and the law maker’s adaptation to the new transportation ecosystem. Having tested the game and its algorithm on a set of numerical examples, the researchers recommend government subsidies for AV manufacturers. This, they believe, will help reduce production costs and greatly encourage manufacturers to produce AVs that outperform human drivers substantially and improve overall traffic safety and efficiency.

How far are we from a true driverless car?

Driverless cars around the world are mostly “partially self-driving” as opposed to being “fully autonomous”, or equipped with the Level 5 automation. The latter implies full automation in all conditions as defined by SAE International–the US-based association that develops global standards for the mobility industry.

Autonomous minibuses are already providing passenger services in countries including Norway, Sweden and France, according to KPMG’s 2019 Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index (AVRI)–a tool to help measure 25 countries’ level of preparedness for autonomous vehicles.

Another early adopter of AVs is freight. The Netherlands, for example, is working with Germany and Belgium on establishing ‘truck platooning’ — where one human-driven vehicle leads a convoy of autonomous ones — on major roads. One of the greatest benefits in efficient road use will come from public authorities being able to track and optimize the flow of vehicles, the KPMG report adds.

Singapore also announced that three areas–Punggol, Tengah and the Jurong Innovation District–will use driverless buses and shuttles for off-peak and on-demand commuting from 2022. It is working with the Netherlands on an international standard for AVs. On 1 January 2018, Norway legalized AV testing on public roads.

Sweden, too, is experimenting with electric-charging roads, AV trucks and driverless buses. Finland is focusing on getting AVs to work in winter conditions and automated bus services–and is repainting the yellow lines on its roads to an AV-friendly white. The UK and Germany, too, are working on AVs.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government (ranked 20th on KPMG’s AVRI) allows first approved AV tests in 2018, with large number of local companies working to compete globally. In India (ranked 24th on KPMG’s AVRI), several Indian start-ups are working on developing AV products for trucks, minibuses and cars, in some cases with a focus on exporting to other countries.

Reality check

Elon Musk boldly predicted during the Tesla Autonomy Investor Day in 2019 that he expects the steering wheel to be done away with in a few years. However, according to a CCN report, the Tesla CEO “softened” his “claims by saying Tesla will have a million “robotaxi-capable” cars on the road by the end of 2020”. Musk had earlier promised that a million driverless cars would operate as taxis and make their owners money.

Apple, too, has reportedly cut over 200 employees from Project Titan, its stealthy autonomous vehicle initiative, people familiar with the group told CNBC.

The fact remains that while companies like Tesla, GM, Ford, BMW, Diamler, Volkswagon, Google (Waymo) and Apple are putting their might behind AVs, a June 20, 2018, report by AlixPartners cautions that the automotive industry “faces the possibility of a monumental capital drain in the near term” as hundreds of players, including non-traditional ones, are pouring unprecedented sums into electric and AVs years before those technologies are fully cost-competitive in the market.

That said, AVs will certainly see the light of day and it’s best to be prepared with a liability draft.